Ever wonder how predictions turn out? When it comes to predictions about greenhouse gases, it's actually a case of great news and lousy news.

First the great news:

- Between 2005 and 2016, while the US economy grew by 17%, energy usage during that time actually was flat, yet CO2 emissions decreased by 14%;

- Sulphur dioxide emissions have decreased by 82% since 2005;

- Carbon dioxide emissions from coal are now back to the levels they were in 1978;

- Carbon dioxide emissions related to electricity generation are down 25% from 2005 levels;

- Energy costs now represent only 4.5% of household spending, the smallest share ever recorded.

Whether or not you believe in climate change (and I definitely do), you should find these data, as reported by the Natural Resources Defense Council, to be very encouraging.

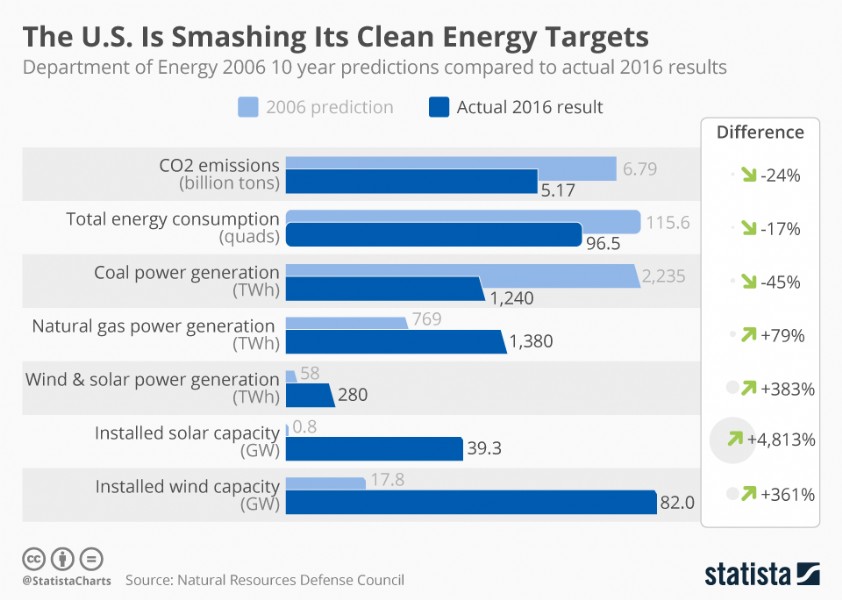

So what could be the lousy news? It turns out the predictions made around 2006 for what 2016 would turn to be were wildly inaccurate. Consider the chart above:

- The 2006 prediction for CO2 emissions was 24% higher than the actual result, meaning that we actually reduced emissions substantially below where we expected;

- The 2006 prediction for coal power generation was off by nearly half;

- Installed solar and wind capacity turned out to be far higher than forecast.

This represented just a ten year prediction, and the prediction was pretty inaccurate. Fortunately, it went in a favorable direction.

These predictions are made every two years by the US government's Energy Information Administration. Those who have studied the projections report that the projections are consistently wrong, sometimes spectacularly wrong.

But it would be unfair for me to single out the people who made these energy predictions. That's because the field of "lousy predictions" is quite crowded. Consider some of the following:

- A study done at Hamilton College in New York about the accuracy of the predictions of political pundits found those predictions were no more accurate than a coin toss.

- Governments tend to do a lousy job of picking high tech enterprises to back, what's sometimes referred to as "industrial policy". Anyone remember the solar power company Solyndra?

- If someone in 1987 was predicting what 2017 would look like, do you think they would have predicted any of the following:

.. The demise of Japan as America's top economic competitor, replaced by China?

.. The rise of the Internet, from an academic/military project almost to the backbone of the world economy?

.. The ubiquity of mobile phones?

.. The growth of renewable energy?

.. The reality of electric powered autos and airplanes?

Unfortunately, our record of making predictions about technology, as well as its impact on society, is about as good or bad as that of political pundits.

There is one big exception: Moore's Law. Gordon Moore first formulated this "law" – that the number of transistors on a chip would double about every 18 months to two years – back in 1965, and the projections have been accurate for 50 years.

Which leads me to believe that the only three things we can really count on are the usual death and taxes, and also Moore's Law. Most every other prediction should be taken with the proverbial grain of salt.

Much beyond Moore's Law, our capacity to predict the impact of technology on our future is pretty lousy. I think this observation can be applied across many technology topics, but I'd like to limit the discussion to greenhouse gases and global warming. So what are the implications?

The first, of course, is that we should take our forecasts of what the world will look like in 2027 and 2047 not with a grain of salt but rather with a heaping portion. Maybe we should simply ignore them. Not because they were poorly constructed and not well thought out, and not because the underlying science is bad (it isn't), but rather because there may be simply too many variables. Let's go back and consider why some of the 2006 predictions were so far off.

One likely explanation is the large substitution of natural gas to replace coal in electric power generation. The chart shows a giant substitution. Why did this happen? The key reason is because natural gas prices went down so much. And why did those gas prices go down so much? It was because of the fracking revolution.

Not many people predicted that. Instead, you may recall, a few years ago there were predictions of "peak oil", meaning that the world was at, or near, its peak potential production of oil and that production would soon permanently decline. I haven't heard much discussion of that idea recently.

Another is because wind and solar have had much greater acceptance than was predicted. Hopefully, the current 2027 and 2047 are similarly understated.

The reduction in total energy consumed was definitely greater than expected. One might argue that that was the result of lower than expected economic growth beginning in 2008. Perhaps. However, a more likely explanation is that business and industry continue to get more efficient. The lean manufacturing revolution has certainly had an impact in that regard. Another reason is because of the greater role of services, and relatively lower percentage of manufacturing, in the economy. The USA produces as much as it ever has, but it's doing it today with far fewer workers and other economic inputs. Huge amounts of waste have been removed from processes. Increases in efficiency explain why households are allocating a record low percentage of their budgets to electricity use.

Not only do we do a lousy job of predicting the future, we humans also tend to do a lousy job of preparing for distant events. Maybe that's because we're so good at responding to immediate threats and dangers.

Why are we so good at responding to immediate threats? It's because we're genetically hardwired to do that. After all, when confronted with immediate threats, such as poisonous snakes and predatory animals, humans are very adept at rapid black and white thinking. We may occasionally over react, but better to do that and still be alive than to under react and wake up dead. Doubtless, a number of ancestors didn't respond quickly, and failed to pass their genes along. We're the progeny of those who were very effective at responding to danger, real or perceived.

But what's the typical reaction when the average person learns that something they're doing today could create a problem in ten, twenty or thirty years? How most people approach diet and exercise should be instructive. For most people, making changes to diet and exercise today in order to prepare for a problem that will likely occur in ten to thirty years doesn't get much response. Do you really want to pass up that nice dessert after your dinner this evening in order to prepare for a potential problem with diabetes in 10 or 20 years? Yes, a certain percentage of the population will do that, but most people don't.

Survival for humans, like all other species, has always depended upon successful reproduction from one generation to the next. What might happen in 30 to 50 years just has never been relevant … until maybe now. Genetically, however, every species is equipped to deal with only the next generation, not the distant future.

So based upon all of this, when it comes to predictions about the future climate, I recommend the following:

Tune in ESPN's Sports Center or HGTV and Turn Off CNN, Fox, and MSNBC

Why turn off CNN, Fox, MSNBC and their brethren? Because based upon what I've pointed out, there's nothing particularly authoritative about what they're saying. If their predictions are about as accurate as a coin toss, why not just get out your Ouija Board? Notice, I'm not saying one network is right and the others are wrong. The predictions of both progressives and conservatives are almost uniformly lousy. Unless you're watching them for the pure entertainment value, if you want to watch politics, try C-SPAN.

Now if you're just watching TV for entertainment, consider what we do at my house: my wife watches HGTV and I watch SportsCenter on ESPN. With hundreds of channels available, I'm sure you can find entertainment without the pretense of authoritative prediction.

Now if you really do want to get the 2027 or 2047 predictions of the energy and climate parameters shown above, given everything I've said above, you may be searching for your version of the Holy Grail.

So does that mean everyone should just give up and tune out? No, while we're pretty lousy at predicting the future, we're actually pretty good at creating it, if we focus our attention in the right places. So with respect to climate change, what are those "right places"? Let me suggest several of them.

#1: Encourage Funding of Basic Research, Technology, and Business Startups

If you look back at why things didn't turn out, a key reason has to do with technological change. Changes in fracking technology, as well as wind and solar technology, have profoundly re-ordered energy markets. Then there's Elon Musk and Tesla. Anyone want to claim they predicted that? The investments that get made in technology will likely have a big impact over the next 10 to 30 years. So how do we encourage this? Here are several ideas:

- Encourage funding of basic research at NASA and DARPA

- Encourage basic research at universities and other institutions

Why NASA and DARPA? Many technological innovations have been spun off from the space program over the past sixty years. DARPA has conducted lots of research on behalf of the US military. DARPA really did help create the Internet. Both entities have produced impressive results that have been commercialized. Moreover, both Democrats and Republicans seem to like NASA and DARPA.

Another idea is to encourage business start ups. Silicon Valley is, of course, the model here, and what's come out of Silicon Valley really impacted change between 1987 and 2017.

But we should be encouraging this all over the country. A recent book by Ross Baird, entitled The Innovation Blind Spot, suggests that there's a great deal of innovation happening in places other than Silicon Valley, New York, and Boston, but we're overlooking much of it. In fact, the next big idea may be from Santa Fe, not San Jose, if we would just pay attention.

#2: Focus Regulatory Change Efforts at the State and Local, Not National Level

Unless you just arrived from Mars, you know that government at the federal level in the USA is grid-locked. Each side blames the other one. It's not likely to change any time soon. Liberals and progressives have been whining that President Trump took the USA out of the Paris Climate Accord, and that there's a systematic effort afoot to deny climate change by the Administration.

Probably so. So what are we going to do about it? I say, stop whining and focus on what can be done. Change may not be practical right now at the Federal level, but there's huge opportunity at the state and local level. Here are some ideas:

- Change building codes, which are local level, to encourage more environmentally friendly building materials. We often forget that building materials make a huge contribution to greenhouse gases. Lots of possibility here.

- Take a cue from people like former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who led a major effort while mayor to reduce greenhouse gases in New York.

- Change how public utilities are regulated. Most utility regulation is state and local.

#3: Find Ways to Incentive Businesses and People to Reduce Greenhouse Gases

Recall how I noted that humans do a lousy job of reacting to problems that are 10, 20 or more years in the future, but that we do a great job reacting to the immediate things.

That's part of the problem of getting people to be concerned about climate change. But we humans tend to do a great job reacting to incentives that are right in front of our faces.

So if we want people to react to greenhouse gases, we're much more likely to get a response if we offer an immediate incentive that will bring long term benefits. One possible incentive is to offer electric utilities a higher rate of return on wind and solar installations than fossil fuel ones. Businesses, and individuals, react to incentives that are right in front of them, much more so than distant threats.

Most likely, when we arrive at the year 2026, we'll find that the predictions we made in 2016 are significantly off. If history repeats itself, we'll actually have constructed far more renewal energy capacity by 2026 than we've been predicting. Even better, our CO2 emissions will be a good deal lower in 2026 than we've projected. It's too bad we're lousy forecasters, but on the other hand, we've demonstrated that we're pretty good at creating technology that makes the predictions wrong. So ignore the pundits and focus on the places where real change occurs.